Can the OxVent ventilator help slow the coronavirus death rate?

[ad_1]

Two hospitals in England are testing a ventilator that just two weeks ago hadn’t even been sketched on a piece of paper. The machine is composed of a few dozen widely-available parts and is unique in its simplicity.

The OxVent, a brainchild of engineers and medics at the University of Oxford and King’s College London, is designed to be shipped as a kit that can be put together quickly by hospitals amid the coronavirus pandemic. The pared-down ventilator is meant to satisfy demand at increasingly desperate hospitals in need of basic machines to help critically-ill patients breathe.

It was designed, prototyped and now tested in the course of just a couple of weeks. Major manufacturers in Europe and the U.S. have discussed production with the team, which is giving away the design for free, according to Federico Formenti, one of the project’s leaders.

“Simplicity is one of the key features,” Formenti said. “To put it in lay terms, it’s similar to receiving a box from Ikea with 57 basic components and a diagram… that facilitates assembly.”

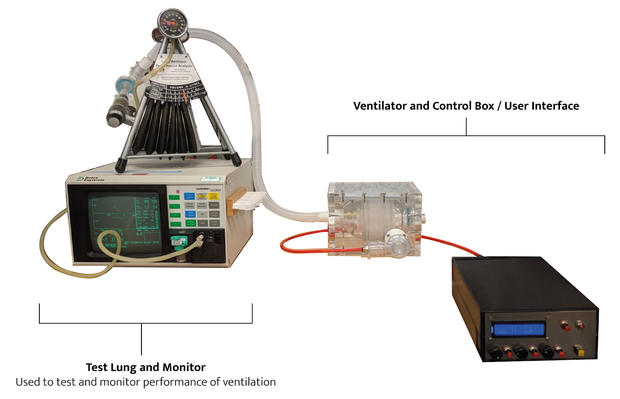

Formenti said he expects the device to sell for about $1,000, far below the cost of ventilators typically found in hospitals, which often go far beyond just ventilation with high-tech sensors built in. Instead, the OxVent is comprised of three simple boxes: a control box to set the rate at which air should be pumped, a transparent container with a pump inside, and a monitor used to track ventilation.

OxVent

Formenti said that while the hope is that manufacturers will sell relatively inexpensive OxVent kits, the goal of the design was to create a ventilator that could be constructed using parts already available to many hospitals.

“We developed this ventilator with the idea that almost any university engineering workshop should be able to manufacture, assemble and test it. So even if there’s no major funding, with open access to the designs they should be able to be manufactured,” Formenti said.

The OxVent is missing many of the features built in to contemporary ventilators, from alarms and diagnostic tools to esophageal pressure measurement mechanisms, which is why its design makes sense for a crisis like the pandemic, according to Per Reinhall, a biomedical engineering expert who is chair of the University of Washington’s Boeing Advanced Research Center.

“From an engineering perspective I don’t see any reason why it would not be possible to refine this design for mass production. This design would of course be (devoid) of some features incorporated in modern ventilators, but I believe it could be very beneficial in regions that are running out of intensive care facilities,” Reinhall said. “The concern would of course be the safety of a kit like this so it would need to undergo a fast-track FDA testing process for it to be used during the current crisis.”

Limitations in the developing world

The coronavirus pandemic has spread to nearly every country in the world, and as cases begin to climb in developing countries, even a device as simple as the OxVent might not be able to help those parts of the world. The OxVent relies on the compressed air that is piped through hospitals in wealthy countries to operate a balloon that pumps oxygen to a patient’s lungs, but that system is less prevalent in hospitals in poorer regions.

It’s a deficiency that may make the OxVent too complex for some still-emerging coronavirus hot-spots, according to Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor Ellen Roche.

“This is an impressive interdisciplinary effort, but their system requires a sealed box with an air pressure supply to compress the Ambu bag. Lots of complexity,” said Roche, a biomedical engineer. She noted that MIT is working on a ventilator model that might eliminate the air compression problem.

In some places, air bags have to be pumped manually by hand — making long-term ventilation difficult to sustain. Formenti said his team is studying another American design to try to address the air compression problem for its second OxVent model.

“I’m very keen to have a mechanical model. There’s a decent example from Rice University… there’s two brackets that squeezed this balloon mechanically. But that approach is relatively more fragile,” Formenti said.

[ad_2]

Source link