Big privacy and data security concerns as India forces coronavirus tracing app on millions

[ad_1]

New Delhi — The Indian government is trying to address privacy concerns raised by hackers, activists, and political opposition parties over its coronavirus contact tracing app. The app, called Aarogya Setu, (“A bridge to health” in Hindi), uses Bluetooth and GPS technology to alert users who may have come into contact with people who’ve tested positive for COVID-19 or shown symptoms of the disease.

More than 100 million smartphone users have downloaded the app since April 2, when the government rolled it out to fight the spread of the new virus. Promotion of the app, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, was so successful that it reached 50 million downloads in just two weeks — one of the fastest uptakes for any app, ever.

India has an estimated 450 million smartphone users among its population of 1.3 billion. To cover more people, the government launched a version of Aarogya Setu for the roughly 100 million cheaper, but still-internet-enabled cell phones in use in the country.

Modi’s government has made the app mandatory for people who work in public and private offices, for all train travellers and for people who live in areas deemed high-risk for the spread of the virus. There’s even the threat of fines and jail terms for people who refuse to install the app in one Delhi suburb.

So far, the app has alerted about 140,000 users to a possible COVID-19 infection risk, the Indian government said Monday.

But while the government insists the app is an important tool in its fight against coronavirus, it has raised concerns over personal privacy and other issues.

“Excessive” data gathering

Concerns have also been raised over how much data the app collects. It asks its users to share their name, phone number, age, gender, profession, and details of countries visited in the last 30 days.

In addition, it asks users to self-assess for any possible COVID-19 symptoms and enter that data daily. The app shows users how many people have symptoms in a particular radius, and how many have tested positive. It sends alerts when a new person near you tests positive, or if someone who was near you previously tests positive.

But the way it does all this has raised concerns.

“The app collects both people’s Bluetooth and GPS [data], which is inconsistent with principles of data minimization. It collects more personal and sensitive personal information than is required,” the Internet Freedom Foundation, a New Delhi-based advocacy group, told CBS News in a statement.

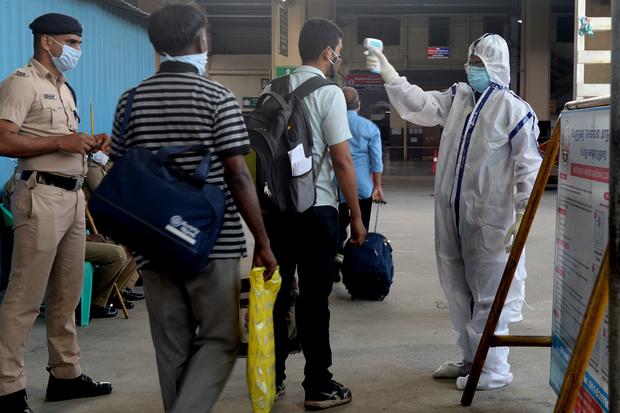

Altaf Qadri/AP

Mishi Choudhary, legal director at the New York- based Software Freedom Law Center, agreed, telling CBS News that collecting GPS data, which records a user’s location every 15 minutes, “along with continuous Bluetooth data is excessive.”

“The Government is yet to publish the application’s underlying source code. Nor has the government published specifications with regard to Bluetooth, cryptography or other technical features. This contrasts with the approaches in countries like Singapore, Australia, the U.K. or even Israel,” the Internet Freedom Foundation said.

“No liability” to protect data

Last week, an “ethical hacker” who identifies himself as Elliot Alderson, an alias inspired by a character in the TV series Mr. Robot, claimed the “privacy of 90 million Indians is at stake” due to “security issues” with the Indian app.

He claimed he was able to use the app to see whether anyone was sick in private homes – including the official residence of Prime Minister Modi: “And yes, yesterday: 5 people felt unwell at the PMO office, 2 unwell at the Indian Army Headquarters, 1 infected people at the Indian parliament, 3 infected at the Home Office,” he wrote on Twitter.

Soon after the hacker’s claims, the Indian government released a statement thanking him, but insisting there was “no data or security breach” and that “no personal information of any user has been proven to be at risk by this ethical hacker.”

“Alderson” had previously raised red flags over alleged security flaws in India’s national biometric identification system — the world’s largest — which has gradually gone from voluntary to near-mandatory in the country.

Choudhary, of the Software Freedom Law Center, said that while India’s government has addressed some concerns, “several matters remain open,” including the lack of government liability to protect data gathered by the app.

She said a clause in the official policy “exempts the government from liability in the event of ‘any unauthorized access to the [user’s] information or modification thereof.'”

“This means that there is no liability for the government, even if the personal information of users are leaked,” said Choudahary.

India’s Communications, Electronics and Information Technology Minister Ravi Shankar Prasad has said Aarogya Setu “has a robust data security architecture.”

How does it compare?

“India has no national data privacy law, and it’s not clear who has access to data from the app and in what situations,” researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have said in a review. The team at MIT ranks various COVID tracing tracker apps around the world for their transparency and other factors, and Aarogya Setu met just two of its five criteria.

“There are no strong, transparent policy or design limitations on accessing or using the data at this point,” the researchers say, while noting that India is the “only democracy making its app mandatory for millions of people.”

Systems being used in Singapore, Australia, Norway, Israel, Czech Republic, Iceland and Austria all scored a perfect 5 on the MIT index, which reviewed apps implemented by a total of 25 countries.

Only China, which failed to meet any of the criteria due to the complete secrecy of its app, and Turkey, Bulgaria, France, Ghana, Iran, Ireland, and Malaysia — which all met just 1 of the 5 criteria — have worse scores than India.

The U.S. hasn’t yet rolled out a national tracking app, but the government is working with technology companies to get one into use.

“Sophisticated surveillance system?”

Some fear India’s app could be used in a way that would violate civil liberties, including by helping to build a state surveillance system that could be exploited after the app outlives its coronavirus-tracking purpose.

Indian opposition leader Rahul Gandhi has called the app “a sophisticated surveillance system, outsourced to a pvt [private] operator, with no institutional oversight.”

“In Europe, the data has largely been aggregated and anonymized,” noted the MIT Technology Review.

Concerns that the app could be used as a surveillance tool come with the backdrop of an existing trust deficit between the government and many citizens. Hundreds took part in protests, which turned deadly, against the government’s plan to roll out a National Register of Citizens (NRC), along with a new citizenship law widely criticized as racist for singling out Muslims.

Concessions, and expansion

As coronavirus cases in India mount — over 82,000 cases and 2,600 deaths so far — the government has tried to address concerns about its tracking app.

On Monday, the government said it would give users an option to seek deletion of their data within 30 days of making a request. It also issued new data processing “guidelines” to various agencies involved in controlling the spread of the virus, banning storage of data for more than six months and warning violators they could face jail time.

“Lot of work has been done over data privacy. A good privacy policy has been made to ensure that personal data of people are not misused,” Ajay Prakash Sawhney, an official with India’s Ministry of Electronics and Internet Technology, said Monday.

Without a national data protection law, however, the concerns over the app’s privacy and data safeguards — and its mandatory use for millions — won’t easily be laid to rest.

India’s parliament has been considering such legislation since last year. The man who wrote the draft, Justice B N Srikrishna, a former Supreme Court justice, told The Indian Express that the government’s move to make the app obligatory for so many people was “utterly illegal”.

“Under what law do you mandate it on anyone? So far it is not backed by any law,” said the former judge.

ARUN SANKAR/AFP/Getty

The New Delhi based Internet Freedom Foundation has challenged the legality of an order by authorities in the Delhi suburb of Noida making installation of the app mandatory for everyone, and threatening violators with possible fines, or even jail.

The government, meanwhile, is considering expanding the mandate for the app. It already covers all train travelers, and it may also apply to air passengers once the world’s biggest COVID-lockdown lifts and flights resume.

[ad_2]

Source link