It’s A Sin star Nathaniel J Hall on contracting HIV at 16 and the ‘unhealed wound’ of the AIDS crisis | Ents & Arts News

[ad_1]

*This article contains spoilers for It’s A Sin*

“There’s a lot of boys who are going home these days,” agent Carol tells young acting hopeful Ritchie, after revealing his ex-boyfriend, Donald Bassett, is one of them. “More and more of them. Every month, going home. And I don’t think we’ll ever see him again, do you?”

Donald’s fleeting appearance in episode three of It’s A Sin is indicative of so many stories of young men growing up amid the AIDS crisis in the 1980s. One minute he is in protagonist Ritchie’s life, flirting, amicably competing for roles, being teased by his friends, falling in lust and love, ditching a condom when it spoils the mood; the next he has simply “gone home”.

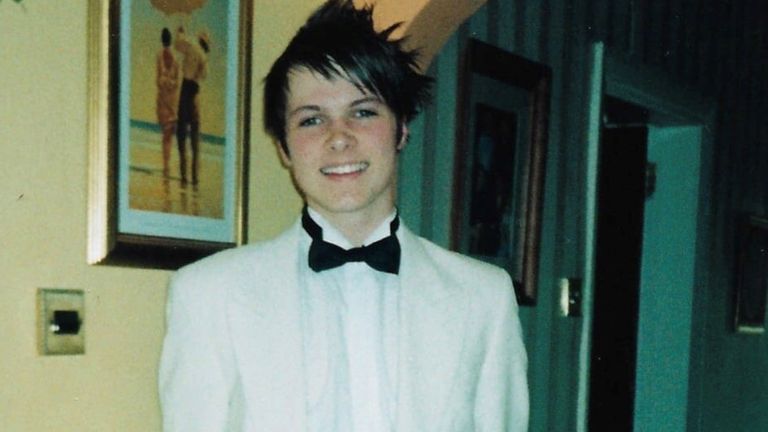

For Nathaniel J Hall, the actor and theatre-maker who plays Donald, in a different time this could have been his own story.

Now 34, Hall contracted HIV when he was just 16, from the first man he ever had sex with. Growing up in the late ’80s and ’90s, he had heard of HIV and AIDS but, at that age, it wasn’t really on his radar as something that could affect his own life. Sex education in school was “pretty much non-existent”, and the UK was still living under Section 28 of the 1988 local government act, banning the “promotion” of homosexuality by councils and schools.

“When I was offered the test, actually, I refused, because I just thought I couldn’t possibly have caught it,” Hall tells Sky News. “You know, I’m white, middle class, I was head boy at my school, I was like, it doesn’t happen to people like me, which is obviously a really ridiculous attitude to have because it can happen to anyone.

“But, yeah, I think it really wasn’t on my radar and there was a denial there because of the fear.”

Hall, who had only just dealt with coming out as gay, was given a life expectancy of around 37 to 40. He says it took him 15 years to come to terms with the diagnosis.

“I was diagnosed very, very young,” he says. “There was a lot of working through all that shame of being gay and trying to unpick all that homophobia that I’d internalised. And then [came] this other thing, I’d contracted this virus.

“I didn’t tell anyone, I didn’t tell my family and my friends – I told very few friends – until about 2017. And I think I thought I was dealing with it. You know, I just boxed it up, put it on a shelf, it was fine. I was like, it’s my life, it’s my medical record, I don’t need to tell anyone.

“But in 2017, I was in a really bad place. I was deeply unhappy and there was this anxiety and all these things that had been not dealt with. It was the trauma of what had happened to me when I was younger.

“I was given a life expectancy of around 37 to 40 years. To hear that at such a young age was very difficult. And I lived with the thinking that I could pass the virus on. I lived with that fear, always, that I could pass it on to a partner, until about 2016 when the science was showing that I couldn’t pass it on.”

Hall decided he needed to make a change. He told his family and went on to make his solo show, First Time, about his experiences. It was like therapy, he says, and he is now able to speak comfortably and openly about his diagnosis.

Which is why he’s chatting to me on Zoom. Monday 1 February marks the start of National HIV Testing Week, as well as LGBT+ History Month in the UK. The government’s goal is to end new cases of the virus by 2030 – but to do this, routine testing needs to “drastically” increase, according to the Terrence Higgins Trust.

New data from the HIV charity, based on YouGov polling of more than 2,000 adults, shows just one in five people (20%) have ever been tested for the virus in the UK, and the Trust estimates there are about 6,000 adults living with HIV undiagnosed.

Of those who have been diagnosed, despite the fact heterosexual men and women made up almost 40% in 2019, uptake for testing is far lower among this group – with just 16% of those polled having previously tested, compared with 58% of gay and lesbian respondents.

Hall is working with the charity to “counter all the myths and scaremongering from the 1980s” about the virus. While It’s A Sin has opened up the conversation, things have changed dramatically since the “exotic disease” shown in the series was first reported in 1981.

In the ’80s and early ’90s, most people with HIV were eventually diagnosed with AIDS. Now, thanks to modern antiretroviral treatment, very few people in the UK develop serious HIV-related illnesses. And HIV negative people are able to take PrEP, an antiretroviral medicine that stops the virus replicating in the body.

Medication has got progressively better, says Hall, whose experience has gone from having to take multiple tablets down to just one a day. The side effects have also “hugely reduced”, he says, and “people like me can’t pass on” the virus.

“Now I’m in a relationship with somebody who’s HIV negative and he takes PrEP, I take my medication, and we have unprotected sex, we have sex without a condom. If I think back to my younger adult years, I can’t even imagine this being the case. It’s a revelation.”

As an HIV activist, Hall says he is very aware that his is the “archetypal” story of someone with the virus. “I’m a white, cis-gendered gay man and that’s the story that we see around HIV quite often.” He is keen to raise awareness that it can affect anyone.

“The gay community particularly has been quite at the forefront of the early part of the HIV and AIDS epidemic because it disproportionately affected gay men,” he says. “In certain communities, it is more stigmatised. I think in the gay male community, whilst stigma and HIV discrimination still exist, I think we’re… often it’s easier if you’re a gay man to say it or talk about it.

“So I try and use my platform wherever I can to remind people that there are other people – women, heterosexual men, you know – that live with HIV and maybe are struggling to be open about that. And actually what we need to do as a society is make them feel comfortable enough to step forward and say it, and say it openly and loud and proud if they want to.”

While the script for It’s A Sin was written before the COVID-19 pandemic took hold, the comparisons are striking. We see patients isolated and medics in PPE, not knowing what we know now, that HIV cannot be passed on by coughing or kissing or general contact. While the world has quite rightly rushed to find a solution to the current pandemic, the response to HIV was very different.

Early on, AIDS was known as “GRID” – gay-related immune deficiency – and terms such as “gay plague” were used. While times have changed, there is still a great deal of stigma around HIV.

“I try to imagine what the HIV and AIDS epidemic might have been like if it had happened today,” says Hall. “But I think we’ve got to remember that HIV predominantly is transmitted through sexual contact or through intravenous drug use and there’s a lot of shame and there’s a lot of stigma associated with those things, and particularly with gay sex.

“I still think it wouldn’t quite have been dealt with in the same way [as COVID-19], because we still have structural and systemic homophobia within our society. And some of the attitudes that we see in It’s A Sin, I think, still prevail today.”

Now testing for a virus has become normalised due to the coronavirus crisis, the hope is that testing for HIV will, too. Terrence Higgins says new figures from Public Health England (PHE) show that between January and August last year there was a 14% increase in at-home HIV testing via online orders, compared with the same period in 2019. However, there was a drop in overall testing in the first half of 2020 as a result of lockdown.

“I think there’s [still] a lot of fear around getting a test,” says Hall. “I think it’s all about normalising it and not making people feel afraid.”

And now, thanks to It’s A Sin, “all of a sudden, everybody is talking about HIV”. The reaction to the drama cannot be overstated, with social media flooded with praise from celebrity fans, critics, viewers, and, most importantly, gay men and women and those with HIV who lived through the era. Writer Russell T Davies‘s drama is devastating and stark but also joyous, warm and funny, with characters who feel like your friends within just a few minutes of meeting them.

Subscribe to the Backstage podcast on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Spreaker

Hall, like Davies and the rest of the cast, has been inundated with messages, as well as requests for interviews such as this. So many in fact, that his boyfriend has set up a spreadsheet. “I never thought a spreadsheet would be a romantic gesture,” he laughs.

“I think what’s really struck me is that for lots of gay men who lived through that period or lots of families who lost loved ones or people who lost friends, I think it’s an unhealed wound. I think it’s reopened that and that’s obviously quite difficult and painful, but I think it’s been cathartic.

“I think what’s very evident is that there is a lot of unresolved trauma around HIV and AIDS. There’s a lot of people who have not had a chance to express these things. You know, as we see in It’s A Sin – no spoilers – but boys just going home and friends never finding out what happened to them, that’s a really awful thing to have gone through.”

Hall says the series has provided a platform to “put all those new messages out there and let people know that HIV is not a death sentence”. Thanks to medical advances, he no longer has to worry about the prognosis he was given when he was a teenager.

The message now, he says, is that “if you get it, you’re going to be fine, with the right support. You’re going to be happy and healthy”.

As we say goodbye, Hall mentions that he lives with his parents and is talking to me from his childhood bedroom.

“It’s slightly surreal doing all this, all this stuff happening now,” he says, of the publicity around It’s A Sin. “If I go back to when I was 16, 17, going through that diagnosis…

“If I could go back to that version of myself, you know… It turns out all right in the end.”

It’s A Sin airs on Fridays at 9pm on Channel 4 and is available to stream on All 4. Free HIV self-sampling test kits are available from the It Starts With Me website and support is available from Terrence Higgins Trust’s free, confidential advice line – 0808 802 1221

[ad_2]

Source link