INVESTIGATION: ‘Bloody’ Farmlands: Inside Plateau Communities Where Killer Herdsmen Hack Helpless Farmers To Death

[ad_1]

Mining pond in shared by locals in Ruku and Tenti, Bokkos LGA serves as a source of water to locals and herdsmen.

Fertile plain and valley in Bokkos LGA.

Rubble of Nghakudun where 30 people died after an attack by armed herdsmen.

Sacked ghost-village in Bokkos LGA. Locals say it was attacked for it's farmlands which have now been converted to a grazing patches by herdsmen.

Cecilia Iliya returned to her village to rebuild after staying at an IDP camp for over a year without government aid.

With no alternative diet, Cecilia Iliya and her children eat corn meal and Baobab soup prepared inside their damaged hut.

Samaila Mahan, 76, sleeps on the bare floor in his damaged hut.

James Luka is the only returnee in his village which was attacked in June 2018.

Deserted classroom in Ganda Mandung. The last lesson taught before the attack by Fulani herdsmen on March 8, 2018 remains scribbled on the board.

SAF Daffo's Palace, Bokkos Local Government Area, Plateau State.

Kitchen area of COCIN Central Church Bokkos which caters for displaced villagers.

Some displaced surviving members of Ruku Village in Bokkos LGA

Steve Mahanan from Ruku was set ablaze during the attack on his village.

Eroded roads like this one in Daffo characterise most paths in the Bokkos interiors.

Makut Macham, human rights activist and local politician.

“This place we are going, do we have security?” The question came through my phone, and immediately I went numb. I hadn’t thought of it, the need for security to safeguard my life as I visited Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) who were supposedly in care of the Nigerian government.

“Hello?” the voice came again, jolting me back to life.

“What do you think?” Makut Macham, my guide, queried.

“No I don’t, let’s just go. If I perish, I perish.” I said half joking, half dreading what was to come.

“Can you do it?” I asked.

“Why not?” he said, and with that the phone dropped.

Armed with puffy jackets against the bone-freezing, wind-bellowing 8°C temperature, the paved journey from Jos in search of the truth hidden in remote strings of villages in the Bokkos wilderness carved into mountains and overseeing boundless lush plains took approximately 2 hours 30 minutes.

It did not take long into the journey before we encountered machete-brandishing and sometimes gun-wielding Fulani herdsmen grazing at GanaRop, a picturesque mining community interrupted only by a military checkpoint installed after complaints by travellers that they were being ambushed by the herdsmen, robbed and sometimes killed.

Mining pond in shared by locals in Ruku and Tenti, Bokkos LGA serves as a source of water to locals and herdsmen.

Mining pond in shared by locals in Ruku and Tenti, Bokkos LGA serves as a source of water to locals and herdsmen.

The armed herdsmen, I was told by Christopher Maren, a youth leader in the area, attacked and displaced the locals of the pond filled village.

“They drove their cows into the farms and destroyed all the crops. You can see the shiny roofing sheets; anytime they attack like that, the Fulani will occupy the houses of the people who used to live there and replace the roof with shiny sheets. That’s how they mark a territory they have taken over.”

The middle belt region of Nigeria where Plateau State sits has witnessed an increased vicious circle of violence perpetrated by the Fulani from 2011till date. The attacks, according to a research by OpenDoors, is fueled by internal migration resulting from environmental degradation caused by the climate crisis.

Since March 2018, Fulani herdsmen, also known as the Fulani militia, have led coordinated attacks on more than 21 villages within Bokkos Local Government Area of Plateau State, leaving more than 100 people dead and about 5000 people permanently displaced from their ancestral lands.

The Road Not Taken

We arrived at Morrok, a scantily-populated town which tore us from modernity and relative safety, ushering us into what the locals described a “no-go area” at exactly 2:47 pm. Before us was paradise, literally. Striped, chiseled rocks and tumbling valleys decorated vast green and lush planes that went on as far as the eye could see. It became clear what the bone of contention is.

Fertile plain and valley in Bokkos LGA.

Fertile plain and valley in Bokkos LGA.

We were not welcomed here. Few minutes into our drive on collapsed ridges and dead road paths that held clues to the daily life of its former inhabitants, it became apparent that the new occupants of the half-charred huts with shiny roofs had become apprehensive. As we made the odd journey, herdsmen armed with scabbards housing lethal daggers and whatever else was hidden behind their jackets started to circle our labouring car.

After missing our way at least two times driving through farmlands that held corn and irish potatoes, which now housed hoofs and stationary dung, we decided to stop and ask one of our profilers who was riding on a motorcycle for the right way, “Which road leads to Nakudong?” we chorused. He pointed an unfamiliar path to the driver and we drove there.

Nghakudun, 2:53 pm. “I remember when this place was first attacked on March 8, 2018, it was terrible and the few survivors didn’t want to go back and bury their dead,” Christopher Maren said as we disembarked from the car.

“We had to call the commissioner of police at the time to come with his men and help evacuate the bodies. The bodies were being packed when the Fulani launched an attack on the CP. The only reason I was not killed that day is that I was the community leader. I was in the car of the Commissioner of Police showing him around. That was how I escaped death.”

Rubble of Nghakudun where 30 people died after an attack by armed herdsmen.

Rubble of Nghakudun where 30 people died after an attack by armed herdsmen.

A similar incident happened on July 8, 2012 with a Nigerian senator, Gyang Dantong, Majority Leader in the Plateau State House of Assembly. Gyang Fulani went to bury their dead constituents after an attack by Fulani migrants on the indigenous tribes in the area.

The lawmakers visited Maseh village in Riyom Local Government Area after the discovery of the remains of 63 persons mostly women and children, burnt inside the residence of a local pastor where they had taken refuge following an attack on about 14 villages by the Fulani herdsmen. The attacked killed at least 50 people.

“Are these herdsmen that we are seeing the ones that launched the attack or was it a strange group?” I asked because at that point, they would zoom past us on motorbikes while others lurked from shrubs.

“Yes, we know them. We grew up together with most of these guys; they know who I am so there is no strange Fulani. Our fathers accommodated them and gave them land a long time ago to graze,” he replied.

Nghakudun stood quiet and bare, reduced to mud, sticks and a stone structure that once housed a church. Ten people died in the attack here.

“The people who lived here were about 400 and above. Nobody is living here, as you can see; most of them have moved to Daffo,” Maren said.

Matio Rock 3:03 pm: I continued in my quest into the plains that were now turning rocky and more difficult to access. As we approached another burnt down and deserted village, one of the locals who accompanied us from Jos but did not want to be named pointed out a rock to me.

“You see that rock, something is happening there. We came with the Red Cross a while ago to assess the situation in the village and when we came, we flew a drone over the rock to get aerial footages and when we were analyzing the footage back home, we noticed a cave guarded by armed men inside the rock,” he said.

“We suspected that is where they keep their arms which they use to attack the villages. We immediately alerted the Special Task Force (STF) Commander and he said he and his men cannot go in there, that it’s too dangerous.”

The surveillance did not stop and at this point, it was too late to go back to seek help in the event that we were attacked by those monitoring our movements, so we continued. Also, there was no mobile network, no electricity, no shop, no town just burnt villages, cows, herdsmen and the Ruga they live in.

Fubok Mandung 3:15 pm: Before it’s sudden demise, the community had embraced modernity and boasted a block of classrooms. After the attack, its furniture, roofing sheets and windows were looted by the herdsmen and then set ablaze, a former resident told me. It was attacked a day after Nakudong.

On our way to the next village, which had just six inhabitants who had returned to rebuild it from the ruins, I counted eight other villages that had been attacked and where people were killed, mostly in the dead of the night.

Sacked ghost-village in Bokkos LGA. Locals say it was attacked for it's farmlands which have now been converted to a grazing patches by herdsmen.

Sacked ghost-village in Bokkos LGA. Locals say it was attacked for it's farmlands which have now been converted to a grazing patches by herdsmen.

Despite the sensitivity and duration of the attacks, which have attracted both national and international attention, no single security presence was visible for the more than four hours we spent penetrating the wilderness.

Ganda Mandung 3:33pm: The chopping sound of axe on wood and the agitated solitary bark of a puppy ushered us into Mandung Ganda where about six people had returned to their village. This place, like all the other villages before it, was razed to the ground by Fulani herdsmen. It also marked a turning point in the story so far, one that shows deception and complete government neglect of IDPs in Plateau State.

In December 2019, the Plateau state government closed 12 camps housing internally displaced persons in the state, sending the victims back to their villages without provision for security or housing considering that their houses were usually razed to the ground when attacks occurred.

When I visited one of such camps at St John Vianney’s Seminary in Barkin Ladi Local Government Area, I was told the camp had been closed and all residents had been ask to go back to their villages. Some however refused to return out of fear for their lives and now work menial jobs to sustain their stay in the town.

Media reports in the Vanguard quote Ezekiel Mandyau, the management committee chairman of Barkin Ladin as saying, “Not really that they are going to any home that has been built for them, not really that they are going back to any farm they had farmed but we think it is better they are home now that there is relative peace.”

In December 2019, Simon Bako Lalong, Governor of Plateau State, also told the Minister of Women Affairs, Paulline Tallen in Abuja: “For those whose houses were not totally destroyed we handled it and asked them to return, that reduced the population of a lot of the population in the camps.”

The statements reveal that the state government, despite benefiting from a N10 billion largesse towards the resettlement of IDPs in Plateau and Benue states since 2018, has made little or no provision to ease the suffering of the victims of the attacks.

Back in Ganda Mandung, Cecilia Iliya is probably in her late 60s but she doesn’t know for sure because she has never had an education neither was her birth ever recorded. She asks me to approximate. Fighting back tears with rapid blinking and swallowing, she narrates how her village was attacked.

Cecilia Iliya returned to her village to rebuild after staying at an IDP camp for over a year without government aid.

Cecilia Iliya returned to her village to rebuild after staying at an IDP camp for over a year without government aid.

“We were living as usual when everything happened. Some of our boys were making blocks from the soil in their farm and a Fulani accosted them and claimed that it is his farmland. The boys were shocked,” she said.

“The Fulani immediately became violent, asking why they were making blocks from their farmland. Our boys responded by saying Fulani doesn’t have land here because they are only nomads who graze according to the season; they come and go.

“The Fulani then hit him with a scabbard and he reacted by hitting him with a stick. It escalated and they started to burn our houses. We had to run; we spent an entire year in Bokkos. This year, we had to return because the suffering was too much; no food, nothing to give the children, nothing.

With no alternative diet, Cecilia Iliya and her children eat corn meal and Baobab soup prepared inside their damaged hut.

With no alternative diet, Cecilia Iliya and her children eat corn meal and Baobab soup prepared inside their damaged hut.

“We begged for farmlands to farm there and earn a living but the locals refused, saying we had to pay, we had no money. Last year, my children said they were tired of suffering in their own land so we decided to return. When we came, we slept on wrappers inside the burnt houses. I decided to come because the suffering was unbearable. If we live or we die, I’ll be here with my children till the end that’s why we came back.

“I know some other villages where people also took the same decision. We have never seen our elected representatives before not to talk of receiving help from them. We vote for them but they don’t care about us.”

A knock on Samaila Mahan’s door caused him to spring up from the earth-coloured wrapper spread out on the bare floor, which he sleeps on. The 76-year-old farmer returned to his destroyed village because, according to him, he was hungry and without much to do in Bokkos town.

Samaila Mahan, 76, sleeps on the bare floor in his damaged hut.

Samaila Mahan, 76, sleeps on the bare floor in his damaged hut.

“It’s traumatic anytime I remember. Look at our houses, lying flat on the floor, we couldn’t do anything because we were overpowered when the attack happened. Our traditional ruler said he tried to mediate; we can only hope for peace. Now that a few of us are back, we have no place to sleep much less put our belongings,” he said.

When I asked if he had received any help from the government to return to his village, his answer was: “No”.

As I exited Mahan’s hut, I happened upon James Luka, a well-built 35-year-old who doesn’t live in Ganda Mandung but in another village across. He said when the attackers raided his village, everyone escaped alive but the village was burnt to the ground.

“They didn’t kill in my village but they condemned everything, our houses; they also slaughtered all our animals. I live in fear. I sleep exposed in cold and in all weather. The government has done nothing.

James Luka is the only returnee in his village which was attacked in June 2018.

James Luka is the only returnee in his village which was attacked in June 2018.

“I couldn’t cope in Bokkos. I have no skills suited for there. All I know is how to farm; this is my home. I prefer to stay in my home even if it means I die,” he said with steely resolve.

While in the village, I saw a block of classrooms which serves as a polling unit during elections. The locals say this is their only contact with government officials, who make the painstaking journey to the village once during electioneering every four years but never return afterwards.

The classroom is now abandoned with roofing sheets stolen by Fulani herdsmen, burnt churches now overrun by wild monkeys litter the village where a community of six people have resolved to return.

Deserted classroom in Ganda Mandung. The last lesson taught before the attack by Fulani herdsmen on March 8, 2018 remains scribbled on the board.

Deserted classroom in Ganda Mandung. The last lesson taught before the attack by Fulani herdsmen on March 8, 2018 remains scribbled on the board.

We passed five more sacked villages after Ganda Mandung on our way to Daffo, where some of the villagers had been absorbed by relatives or church missions.

Maren, my guide, offered to tell me how some of the attacks happened. “You see this community when they attacked it, the people were running towards Daffo,” she said. “Unknown to them, the Fulani had positioned themselves strategically on these rocks; they shot at people from up and from down. It was a terrible night.”

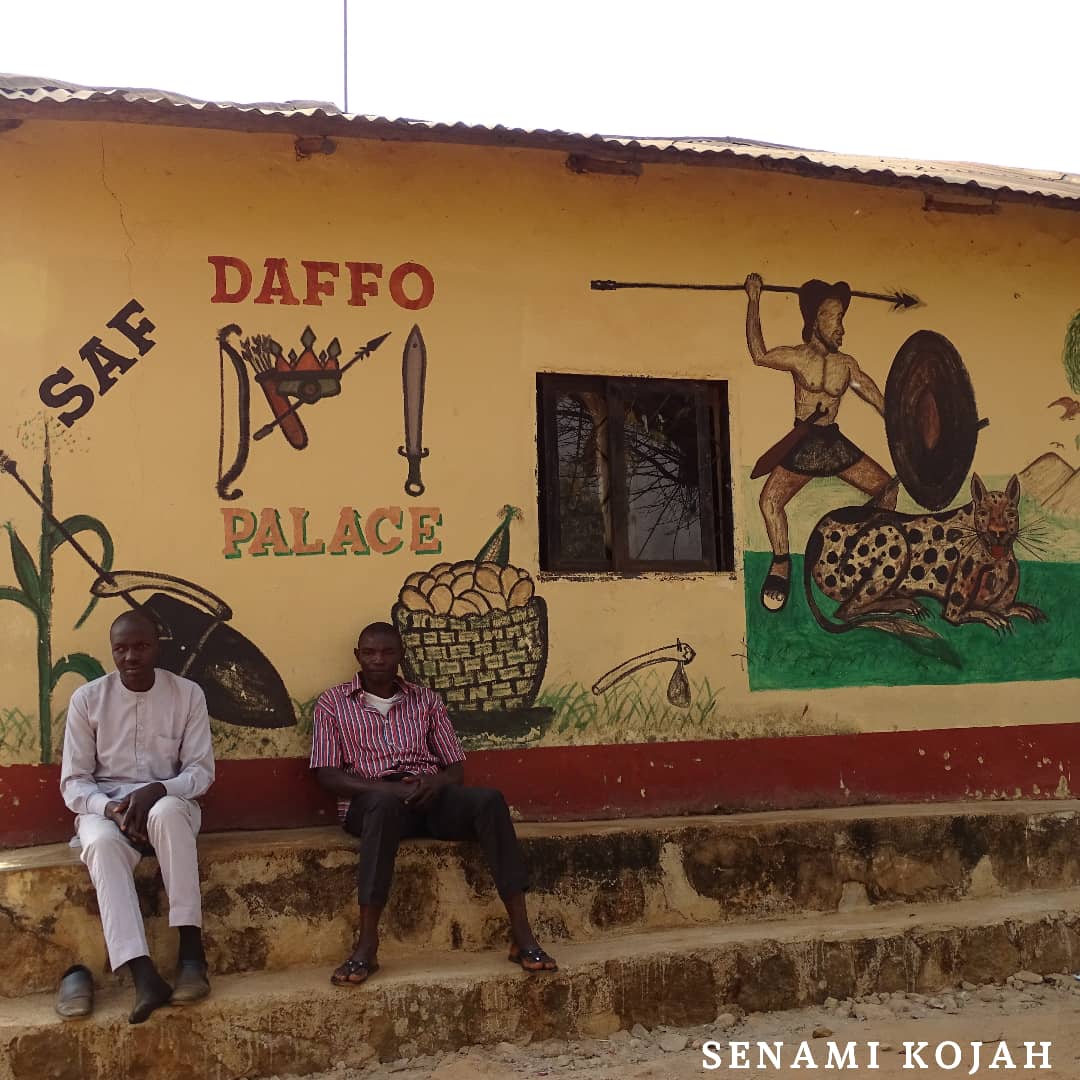

Daffo 5:15 pm: In Daffo, I wanted to meet with the SAF Daffo, the traditional ruler who oversaw all the villages I had been to. A source had confided in me that the local chief connives with the government and sometimes the Fulani to mask the intensity of the situation in the area and he avoids journalists.

SAF Daffo's Palace, Bokkos Local Government Area, Plateau State.

SAF Daffo's Palace, Bokkos Local Government Area, Plateau State.

Upon entering the Palace, I was told he wasn’t around despite the fact that the palace staff had told me he was in his room. I ended up talking to his secretary who assured me that all was well in their communities and that the government was restoring peace to the area.

“Each time there is a breakout of attacks like this, you will hear the government say ‘unknown gunmen’. They are not unknown; they are known already. If we say we don’t know them, then we are fools. I don’t think Nigerians should be fools,” said Reverend Samuel Matawal, Lead Pastor at Church of Christ in Nations (COCIN) LCC Bokkos Central, where I came the next day to see IDPs that had been abandoned by the government but were now taking refuge at the church.

Kitchen area of COCIN Central Church Bokkos which caters for displaced villagers.

Kitchen area of COCIN Central Church Bokkos which caters for displaced villagers.

Packed with people, the church absorbed almost all the IDPs attacked in the villages, only receiving donations from the Plateau State Emergency Management Agency once after that attack. The supplies lasted just one day and the church has struggled to cope ever since.

“We started getting IDPs here from 19th February 2018 from Daffo. After March and April 2018, we tried to get church members to absorb them. There was another influx of IDPs from Kazok, Burdunga and Ruku, and they live here, until now,” Matawal added.

I wanted to meet with some of the IDPs from one of the worst hit villages, Ruku, where 1,463 persons — comprising of 684 children, 411 adult males and 375 women — were displaced.

Some displaced surviving members of Ruku Village in Bokkos LGA

Some displaced surviving members of Ruku Village in Bokkos LGA

Honorable Magwai Peter, Head of the IDPs in the church, said the government had been using the displacement of people to play politics while deceiving the media and the world that relocations were taking place.

He said, “We have suffered. If not for the churches who have been looking after us, we have no one to help. The relocation committee told us to leave our ancestral homes from the Fulani. They said because the terrain is rugged, anytime there is an attack it will be difficult to get security to us.

“No one came out with anything; we lost everything. The same the attack was carried out, the herdsmen grazed on all our farms. But even in the new land they provided, we started building and the same Fulani who attacked our village in Ruku came in the night and demolished everything. They put a red flag on the land, which is a traditional message to stay off.”

Steve Mahanan from Ruku was set ablaze during the attack on his village.

Steve Mahanan from Ruku was set ablaze during the attack on his village.

A local from Ruku who did not want to be named told us the relocation committee inaugurated by the government came with relief materials and journalists who took photos of the items being distributed. He said that afterwards, the relief material was taken by the committee from the IDPs on the guise that it would be reallocated later. They have not heard from the committees since then.

When I reached out to the Chairman of the IDP Relocation Committee in Plateau state, Professor Danladi Atu, about the claims, he did not return a call placed to his direct line and he did not reply a text of inquiry.

In December 2019, Atu told journalists, “We have out in place a machinery to resettle IDPs in the state.”

When I asked Magwai, leader of the IDP’s, he attributed it to politics. “It’s all talk and politics,” he said.

To prove his point, Magwai invited me to Ruku village, some 29.2km and approximately 34 minutes away from Bokkos town to see things for myself.

Valley of the Shadow of Death

On getting close to Ruku, we met more than 100 IDPs who had converged to discuss a way forward in rebuilding their lives. They insisted I see the ruins of their village to fully understand what happened the night 40 were killed.

I hopped on a motorcycle provided by the locals and was escorted by seven others who, though unarmed, volunteered to protect me and my guide in the event of a surprise ambush by the Fulani.

We galloped through the narrow undulating rocky paths dotted with teal green mining ponds and grazing cows. I was told to hide my camera so the herdsmen don’t suspect I was carrying a gun because of the strap. Terrified, I tucked it underneath my jacket to create an uncanny bulge in my tummy.

Eroded roads like this one in Daffo characterise most paths in the Bokkos interiors.

Eroded roads like this one in Daffo characterise most paths in the Bokkos interiors.

After many minutes, we arrived Ruku. It lay bare, with red mud bricks which signified the community that once thrived. Now, here looked like it had been crushed in a deliberate pounding attempt.

“We were in our house when we saw that we were surrounded,” recounted Lydia Sati, a nursing mother who escaped with her toddler. “We packed our children and ran into the house and locked the door. The shootings did not stop. We screamed for help but no one came; they burnt our motorcycle and looted all our belongings. I lost my husband and two children.”

Recalling the events of June 8, 2018 when Ruku village was attacked, Deborah Danjuma said she was shocked when she saw the Fulani she interacts with in her community surround her house and attack it.

“The people who attacked us we accommodated as guests for many years,” she said. “We were sitting at home around 3pm in the evening when we started hearing gunshots. They came ready for war and because we think no ill towards them, we had nothing to defend ourselves. I saw like seven people burn right before my eyes. We don’t have anywhere to go; the government has completely forgotten us.”

As I was conducting interviews in the backdrop of the ruins, the village was surrounded once again by Fulani herdsmen who had been casing since we arrived on motorcycles. A confrontation ensured and I was whisked away by the youth who had accompanied me. I escaped the ambush by speeding through the rocks.

Nura Abdullahi, former state chairman of Miyetti Allah Cattle Breeders Association of Nigeria (MACBAN) in Plateau State told me he condemns the killings in Bokkos.

“It is barbaric what is happening in Bokkos and I condemn it in its totality. I do not support what is happening there because I am a Nigerian with humanity,” he said.

He added that the killing of innocent people by herdsmen in the state is anchored on criminality.

“We should sheath our swords and allow peace to reign in our domains. When we are taking laws into our hands by not allowing others to be in peace, we also will not be in peace. The best thing is to embrace peace which is very sweet. Peace is a proces and everyone must work for it, we must tell ourselves the truth,” he concluded.

A source in the Nigerian presidency said a policy document titled Livestock Alimentation & Rural Management Initiative (LARM) which proposes a comprehensive solution to the Attacks was tabled before President Muhammadu Buhari via Vice President Yemi Osinbajo. The document was however thrown out to make room for the Ruga proposal, which was widely criticized.

The document, calls for indigenous ownership of grazing paddocks by locals who in turn lease it to herdsmen. The move is targeted at empowering the indigenous land owner well as the Fulani herdsmen who will abandon the nomadic lifestyle and whose children can also attend schools.

Makut Macham, an architect and local politician in the area, wondered why the government was ignoring the plight of people in Bokkos.

“I usually wonder why Bokkos is being overlooked in all of this,” he said.

“We are peace-loving and all we want to do is to get by through life, so I am wondering why we are the victims over and over again. Why are we under attacks? What is the function of government? We are not begging government or pleading with the government to do what they are not supposed to do; we are pleading on them to do the constitutional thing.

Makut Macham, human rights activist and local politician.

Makut Macham, human rights activist and local politician.

“What will it take for government to hear the cry of its people? We are demanding justice. The perpetrators of violence should be brought to book. Those who have killed our traditional rulers should be charged to court and they should be treated as criminals. Let’s not get to a point where criminality is seen as a form of bargain or enrichment. Why should our lands be taken from us and government just seats, keeping mum about it? Something needs to be done now, we demand for justice!”

AddThis

:

Featured Image

:

Original Author

:

Senami Kojah

Disable advertisements

:

[ad_2]

Source link