What is xylazine, the veterinary sedative being found in the U.S. drug supply?

[ad_1]

It extends the feeling of an opiate high. It’s hard to detect and can’t be reversed by medications like Narcan. It’s immediately recognizable by the gruesome, scaly wounds that emerge on users’ skin, and can even cause injuries to their lungs. And in some parts of the United States, experts say it’s in as much as 90% of the drug supply.

It’s a veterinary sedative called xylazine, and experts and officials are racing to figure out where it’s coming from and how to help people who are taking it, even as it’s increasingly being identified in overdoses.

“At this point, colleagues and I are trying to crowdsource together as much information as we can, because there’s just no organized network and this drug is so new,” said Claire Zagorski, a chemist, paramedic and translational scientist in Austin, Texas. There’s very little research out there about how it behaves in humans. We’re seeing really rough wounds. … We aren’t going to be able to understand how to prevent or treat these issues if we don’t know what’s going on.”

Experts spoke to CBS News about what trends they’re seeing now, what the risks of xylazine are and how people can help if they are bystanders to an overdose involving xylazine.

What is xylazine?

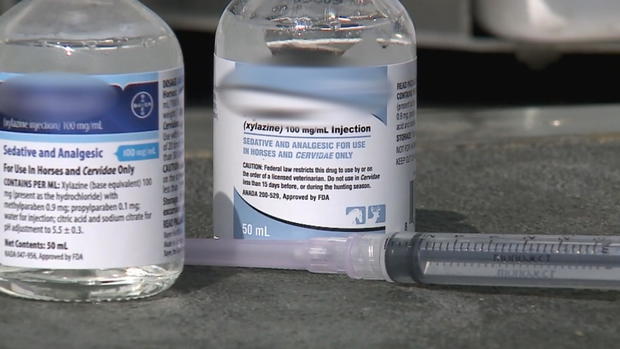

Xylazine is a sedative and muscle relaxer used on large animals like horses, and is not approved for use in humans, said Dr. Sherri Kacinko, a forensic toxicologist at NMS Labs in Pennsylvania who studies xylazine and other substances.

It was first detected being used by humans in Puerto Rico in the early 2000s, said Kacinko, and has been reported in the United States for several years. First reports of its use in Philadelphia emerged in 2008, Kacinko said, with more common use being reported in 2019 — by 2023, it was present in most states in the country, and Jose Benitez, the lead executive officer of harm reduction organization Prevention Point, said it is found in 90% of Philadelphia’s drug supply.

It has been found in multiple overdoses, but because it is combined with other substances like fentanyl or heroin, experts said it was hard to account for how responsible it was for those overdoses.

“It is difficult to know which substance contributes most to fatality when an individual has more than one substance in their body at the time they died,” Benitez said.

In humans, xylazine extends the half-life of fentanyl, the effects of which typically last only one to three hours. With a shorter half-life, people have to use “a lot more often” to avoid withdrawal symptoms, said Alixe Dittmore, a training and content development coordinator with the National Harm Reduction Coalition who provides direct care to people who use drugs. When combined with xylazine, the effects usually last four to six hours.

CBS News

“We say it adds legs. It kind of gives the illusion that your opiate high is lasting longer than it is,” Dittmore said. “When in reality, what’s happening is the opiates have started to wear off of your system around that one- to three-hour mark, depending on your tolerance and use, and then you still have the xylazine, so what happens is people still have that sedative effect and you’re seeing a lot more injuries.”

A recent import alert from the Food and Drug Administration aims to restrict unlawful importing of xylazine, but Zagorski said that it’s unclear where xylazine is coming from, with no obvious culprit or single source of the substance.

“One of the things that makes this really unique and odd is the xylazine we’re seeing in the drug supply is being sourced from aboveground. It’s not being cooked in labs, it’s being diverted from veterinary suppliers, and the specific source of that isn’t clear,” she said. Chemical evidence shows that the xylazine being found is “purely made,” which Zagorski said was “very uncommon for the illicit drug supply, especially at this scale.”

Why is xylazine harmful?

Xylazine is a central nervous system depressant, Dittmore said, which has a sedative effect and depresses breathing. It is not an opiate, but those effects combined with an opiate can stop someone’s breathing, causing an overdose.

People often aren’t buying xylazine deliberately, Dittmore said, making it riskier. Xylazine also cannot be detected with testing strips the way that fentanyl can be, so people don’t know if their drugs are contaminated with it — unless they have access to a costly mass spectrometers, which are typically found in medical settings.

Because of its powerful sedative effects, some people who use drugs mixed with xylazine may also black out unexpectedly, which may lead to them falling or being unconscious in unsafe places, leaving them vulnerable to attack or injury. Dittmore said that she has seen “a lot more injuries,” including head injuries from falling. Zagorski said that people may also experience bed sores from resting on hard surfaces like concrete for hours at a time with no movement.

One of the most alarming side harms, and one of the most-discussed, are the wounds that xylazine use can cause. Dittmore said that the wounds can appear at injection sites, but also in other parts of the body, “most on the extremities” like legs and arms. The wounds will grow if left untreated and can become infected. Unlike abscesses, which are common with injected drugs, xylazine wounds will start out resembling blisters that then open and expand, leading to the risk of infection that Dittmore referenced and growing wider instead of deeper.

The wounds can also become necrotic, and Kacinko said they can progress to cause soft tissue injury. Benitez said that people at Prevention Point have even heard anecdotal reports of the wounds progressing to a point where they require amputation of the limb, and said that area hospitals have reported an increase in visits for advanced skin and soft tissue infections.

Melanie Beddis, the director of programs at Savage Sisters Recovery, a Philadelphia nonprofit, said that she has experienced these wounds herself.

“I first got these wounds three, four years ago, before there was talk of xylazine,” said Beddis, who has used drugs, including xylazine. “And I was confused on what was happening because it wasn’t at the site of where I was injecting drugs and I also switched my consumption method … to see if that would help, and I was still getting the wounds.”

Beddis said at urgent cares she would be diagnosed with a staph infection and be given antibiotics, which often wouldn’t work. Dittmore said that antibiotics aren’t the “first mode of treatment” because the wounds aren’t actually caused by an infection.

Now, as part of her work, Beddis runs a streetside wound care clinic that offers aid to people in need.

“We do the best we can to clean their wound, wrap it up the best we can, give the advice we can, and send them on their way until they are ready to seek medical treatment,” Beddis said. Dittmore said the best way to handle xylazine-related wounds is washing them with a clean cloth, sterile water and plain soap. Keeping the wound soft is key, she said, and applying Vaseline or Xerofoam, both available over-the-counter, can keep the injury from getting worse. Covering it in nonadhesive gauze and then wrapping the injury in an ace bandage can ensure the wound stays clean, Dittmore said.

Benitez said that he has seen lesions on the lungs of people who are smoking drugs tainted with xylazine.

Zagorski said that anecdotal information indicates there may be further issues associated with using xylazine, including anemia and spikes in blood sugar. However, research into these symptoms is still in the early stages.

“We need to figure all of this out. We really urgently need lab researchers to sit down and figure this out on a molecular level, because we aren’t going to be able to understand how to prevent or treat these issues if we don’t know what’s going on,” Zagorski said.

How can bystanders help someone experiencing a xylazine overdose?

Xylazine does not react to naloxone, but that doesn’t mean the opioid-reversing medication can’t be helpful if a bystander sees someone experiencing an overdose, experts interviewed said, because xylazine is used in conjunction with opioids that will react to the naloxone. While xylazine has appeared in fatal overdoses, it’s unclear how much the sedative contributed to the person’s death because it is used in conjunction with the stronger opioids.

“The opiates will be kicked off the opioid receptors by the naloxone, but the xylazine is still there,” Dittmore said.

Zagorski said that giving someone naloxone even when they aren’t experiencing an opioid overdose won’t harm them, so it’s better for a bystander to administer it if possible. Dittmore said that even though the naloxone will reverse the opioid overdose, a person may still be experiencing xylazine effects and may seem drowsy or out of it.

“Because of the sedation effect (of xylazine), it takes people a bit longer to rouse and become alert,” said Dittmore, who said she has reversed dozens of overdoses. “They don’t need to be eyes open, wide awake in order for the overdose to be reversed. You’re just trying to get that breathing to resume again.”

To keep breathing even, Zagorski and Dittmore said, bystanders can try rescue breathing, which is essentially providing mouth-to-mouth on the person who has overdosed. Both said that there is no risk of overdosing on xylazine, or any other drugs that a person may have taken, from taking these steps.

“Rescue breaths are the hugest thing if folks feel comfortable,” Dittmore said. “The sooner you can get oxygen into their body, the better.”

Bystanders should also call 911 or other emergency services, who can help provide medical care.

[ad_2]

Source link