Meet a pioneer in stroke recovery

[ad_1]

Retired New Jersey schoolteacher Holly Ulland and her son, Aaron, always have been exceptionally close. She described her son as “very compassionate, loves animals, has always been a tinkerer.”

Young and capable, Aaron seemed perfectly healthy, until one January morning in 2019.

“I woke up to use the bathroom and I couldn’t get out of my bed,” he told correspondent Susan Spencer. ” I had to grab something to get out of my bed. And then I got my two feet on the floor and I walked just couple feet and I fell down.”

Holly recalled, “I went to go down the hallway, past his bedroom, found him on the floor, but he said he could not get up.”

“This must have been terrifying,” Spencer said.

“Yeah,” Aaron replied.

At just 39 years old, Aaron had suffered a stroke, paralyzing his left side. “He tried to talk to me,” said Holly. “But his words were all gargled. And I was terrified that he’d never speak again.”

After four days in the ICU, he’d regained his speech, but not much else. He then spent two months in rehab. “We had one neurologist tell us that Aaron would never move his arm again. And when we got in the parking lot, I literally put his face in my hands, and I said, ‘Don’t you even buy into that.'”

CBS News

According to Dr. Diana Tzeng, a neurology professor at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, a stroke occurs “whenever there’s any problem with blood flow to the brain. The more common type is caused by some sort of blockage of an artery.”

Spencer asked, “In general people assume that strokes happen only to older people. Is that the case?”

“Anyone can have a stroke, even young people,” Tzeng said. “And there is a concerning trend where there are more young adults suffering from strokes.”

Astoundingly, one American has a stroke every 40 seconds, and 10 to 15 percent of stroke victims are only 18 to 49 years old. As to why this happens. “About 50% of the time, when a young person has a stroke we can’t figure out the cause,” Tzeng said.

The cause of Aaron Ulland’s stroke is still a mystery, but the consequences are devastatingly clear.

Tzeng said, “There is no regeneration of brain cells. Once you’ve had a stroke, the brain cells that have been affected are dead. For some patients we offer intensive physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, but in terms of direct interventions that we can provide to patients, still none to help them regain what they’ve lost.”

But Aaron is determined to regain what’s lost, which is why he mastered a three-wheeler when he couldn’t ride a regular bike … and why he said yes to be Patient One in a revolutionary study at Thomas Jefferson University.

His mother wasn’t so sure. When asked her reaction to being told “We’re going to put electrodes in your son’s brain,” she replied, “Honestly, I was terrified. But I also knew it was Aaron’s decision.”

And he did not hesitate? “No,” Holly said. “He just kept saying, ‘I want my arm back.'”

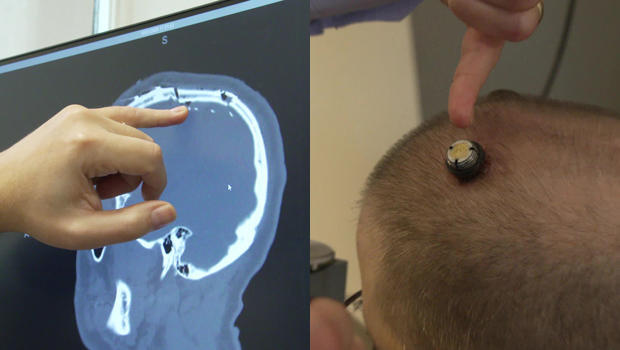

So, last October, with cameras rolling, doctors implanted multiple electrodes in Aaron’s brain. It took nine hours.

Jefferson Health Neurosurgeon Dr. Robert Rosenwasser, one of two lead doctors on the study, said, “We rehearsed this hundreds of times prior to surgery to know how we were gonna do it, to know precisely where we were gonna put it.”

Thomas Jefferson University neurology professor Dr. Mijail Serruya, the other lead doctor, described the electrodes that were implanted: “The electrodes from this study are incredibly small, about the size of a baby aspirin or a regular M&M, so smaller than a peanut M&M. And they just go into the surface of the cortex, the outside of the brain.”

CBS News

The role of the electrodes, said Rosenwasser, “is to record the electrical signals from his existing brain cells, take those electrical signals and convert them into the movement that he desires to do: move his fingers, move his hand, move his arm.”

In other words, Aaron’s stroke damaged the connection between his brain and his arm. These electrodes repair it, sending signals from his brain to a motorized brace. And viola! Aaron can move his arm again!

CBS News

“He’s shown us that someone, almost two years now after a pretty significant stroke, can recover function,” said Serruya.

And it’s just the beginning.

Spencer asked, “There’s so many things that we do that we just completely take for granted, for example, pick up a cup, or he said he has trouble zipping anything because he can’t use that hand. How far do you think this technology can go in terms of people actually regaining fine motor skills?”

“Well, I’m not sure I’ll be on this Earth to see it, but I think we’ll have people playing the piano and being concert violinists,” Rosenwasser said.

Aaron’s electrodes were put in for only a three-month trial. But doctors see the day when – like a pacemaker – this technology will be wireless and implantable, eliminating the arm brace altogether.

Serruya said, “I think that is the goal, that in the coming five, 10, 15, 20 years, we will have a medical device that will be available for people who’ve had a stroke, so that they can go to their physician, their neurosurgery team, get this device, and however far they’ve gotten in their physical and occupational therapy, they can break through that plateau and keep going and restore movement.”

CBS News

Spencer asked Aaron, “Your doctors think that this is potentially a game-changer?”

“Yeah. It’ll help other stroke victims, and they can look at my stuff,” he replied. “Yeah. They call me the pioneer.”

“Yeah. You like that?”

“Yeah!” he smiled.

For more info:

Story produced by Amiel Weisfogel. Editor: Carol Ross.

[ad_2]

Source link