Reaching out: How caring letters help in suicide prevention

[ad_1]

By most accounts Kevin Hines shouldn’t be alive; at age 19 he jumped off the Golden Gate Bridge. “I remember the fall vividly,” he told correspondent Lee Cowan. “Twenty-five stories, 75 miles an hour, four seconds.” Although the fall shattered his back, he survived.

He had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder at age 17, but on that day in September of 2000, it just all became too much. “The night before I was filled with so much agony, so much pain,” he said.

“What was going through your mind?” Cowan asked.

“I had been dealing with this diagnosis for two-and-a-half years. My greatest mistake was lying to everybody who loved me, believing that I was their greatest burden, and if I didn’t die by my hands, that it would ruin their life.”

The sense of loneliness, Hines said, was unbearable. “All I wanted was for one person to see my pain and say something kind,” he said.

“But you couldn’t reach out? You wanted them to reach out?” Cowan asked.

“I could not reach out. I needed someone to reach in.”

CBS News

Just one person stopped him on the bridge that day – a passing tourist who only asked him to take her picture.

“She walked away. I said, ‘Nobody cares,'” Hines said. “The voice in my head screamed Jump now, and I did. If one person had shown me an ounce of care, I would not have jumped off that bridge.”

Could it really be that easy? Is a simple expression of concern enough to cut through the darkest recesses of a suicidal mind? Turns out, some long-forgotten research from a psychiatrist named Dr. Jerry Motto at the University of California, San Francisco says yes.

Motto had served in World War II, and he never forgot the impact of writing and receiving letters while he was overseas. They made him feel more connected, and that gave him a very simple idea: “If you know that you are going to make a connection, and that you can communicate that you care, that’s all that’s important,” said Dr. Motto’s wife, Pat Conway.

That, said Chris Asimos, “is the fuel for wanting to live.”

Asimos and Conway were young researchers back in the 1960s when Motto put together a team to take what was then a pretty unconventional dive into suicide prevention.

When asked how suicide was treated by health care professionals back then, Asimos replied, “Not well. I think all too often the physician thought that this was ‘looking for attention.’ It was not good.”

Dr. Motto theorized that, like him during the war, if people somehow felt more connected in the days after being released from a psychiatric facility – one of the riskiest times for suicide – that might just be the tether that holds them to life.

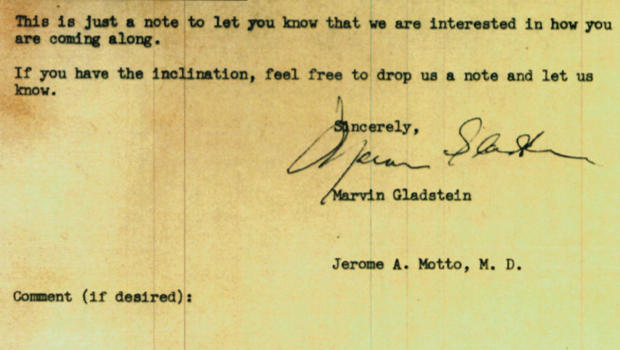

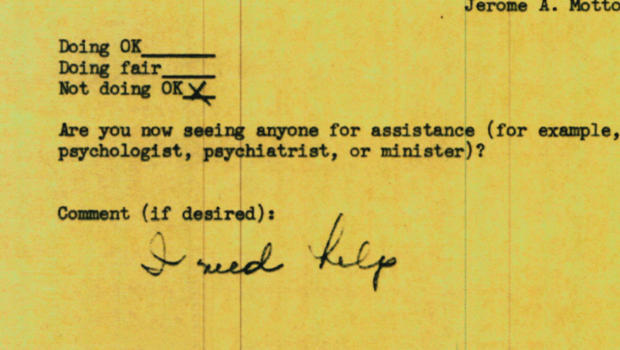

So, he devised a research study involving patients who had been hospitalized for suicide and depression, and had refused follow-up care. Between 1969 and 1974, he sent half of the patients a series of what he called “caring letters.” The other half, the control group, got nothing.

CBS News

The letters, Asimos and Conway said, communicated caring and concern, with nothing expected in return. “Just, ‘We care.’ That’s all. ‘We care,'” Conway said.

“Probably a lot of people thought that’s a bit silly. That’s not going to work?”

“We heard people saying, ‘Oh you’re kidding. One letter is going to make a difference, or a series of letters?'” Asimos said.

But it did make a difference. They actually started getting letters back:

“Getting this letter lightened me very much. It is beautiful to get a letter from you.”

“Your note gave me a warm pleasant feeling. Just knowing someone cares means a lot.”

There was one response, however, that stood out above the rest – what Dr. Motto called the “Bingo Letter” – because it was a hint that they really were getting through:

“You are the most persistent son-of-a-bitch I’ve ever encountered. So you must really be sincere in your interest in me.”

But proving the letters were actually preventing suicide would mean scouring California’s death records housed in Sacramento.

“We would talk about bracing ourselves for the reality that we might find names of patients that we had seen,” Asimos said.

What they found was nothing short of remarkable. In the first two years after leaving the hospital, the suicide rate of those who received the Motto caring letters was about half the rate of those who did not.

CBS News

“He showed that a simple intervention, or any intervention, could prevent suicide, and that’s enormous,” said Ursula Whiteside, a clinical psychologist and researcher at the University of Washington School of Medicine. She said Motto’s research was indeed a breakthrough. And yet, “I feel like in some ways people didn’t notice.”

“If it’s this significant, why?” asked Cowan.

“It’s probably a lot of reasons,” Whiteside said. “One being, like, the stigma around mental health, how small the field was at the time. And I also think that he didn’t go out and push his message, although I really wish that he had.”

Suicide rates in this country have now hit their highest levels since World War II. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports there are now twice as many suicides as homicides, That’s despite the tens of millions of dollars being spent to combat it.

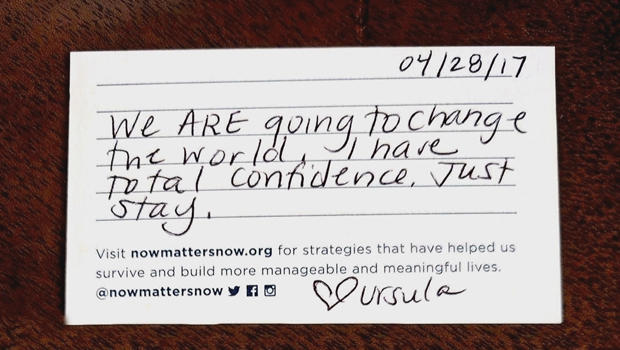

Whiteside said, “This is totally different. It’s the cost of the stamps and the cost of the card. This is radical if you think about it in comparison to what we’ve been doing.”

CBS News

For almost two decades now, Whiteside has been sending versions of the Motto letter out to her patients, like Shannon Lucas, who had been suffering from suicidal thoughts. “I really wanted a different approach. I’ve had previous therapy and counseling experiences, but it felt a little stale,” Lucas said.

“And in all those years, nobody had ever tried this with you?” Cowan asked.

“No. No. It was Make your appointment, show up, see ya’ next time. There was no in-between.”

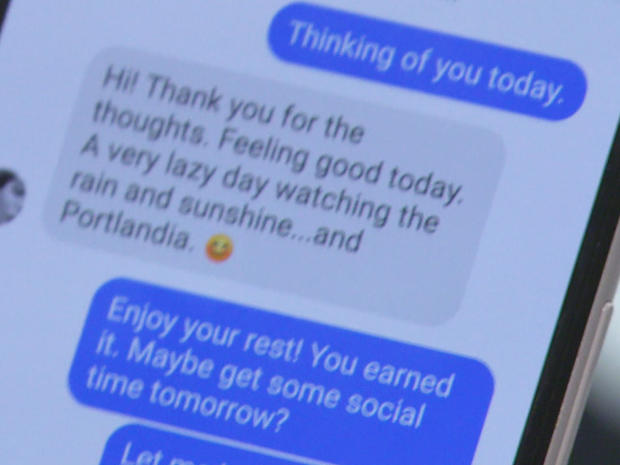

Instead of sending caring letters through the mail, though, Whiteside sent Lucas caring text messages.

CBS News

“She’s telling me what she’s been doing, and I write back, ‘You are on fire,’ and send an image of a woman blowing fire!” Whiteside said.

Lucas described that as “Classic Ursula.”

“Not to take anything away from your texts, but they weren’t these big deep thoughts, right?” asked Cowan.

“No, they were warm and engaging and comforting and sincere,” Lucas said. “Instead of just staying in the same mode of being cut off and shutting down, through her messages I was able to connect with someone.”

Whiteside said, “Loneliness is killing us. Why wouldn’t you be reaching out to the person who’s disappeared off Facebook or maybe the friend who just isn’t acting themselves?”

Dr. Motto died in 2015 at the age of 93. He lived long enough to see a few other people picking up on his long-forgotten idea. The CDC, for example, now recommends caring contacts, and healthcare professionals all across the country also send out colorful postcards with positive messages to those at risk for suicide.

Kevin Hines now travels the country talking about suicide prevention, and the role of caring letters. He knows firsthand of their power, because he got one himself. “It wasn’t about my mental illness; it was telling me that I’m a good person and that I matter,” Hines said.

Cowan asked, “How can that have that big a difference, that big an impact?

“Oh my God! Showing you care about someone – not saying it, showing it – is tangible. When it’s tangible, it means more. So, the one thing we know that does work, we better be using.”

And, he told Cowan, he never takes life for granted: “Oh, are you kidding me? No way. … Every moment is appreciated, every millisecond is grabbed onto.”

YOU ARE NOT ALONE

If you are in crisis, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255), or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741.

For more info:

Story produced by Deirdre Cohen.

See also:

[ad_2]

Source link