Veteran dies of treatable illness as COVID fills hospital beds, leaving doctors “playing musical chairs”

[ad_1]

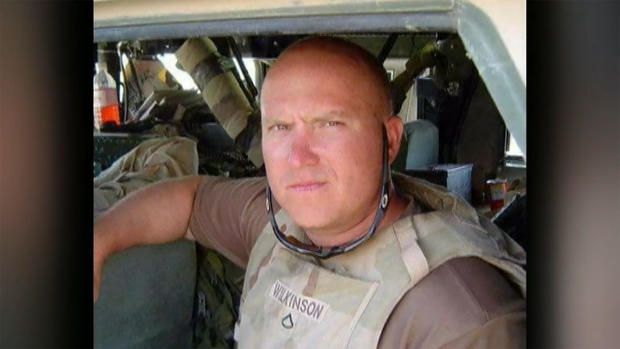

When U.S. Army veteran Daniel Wilkinson started feeling sick last week, he went to the hospital in Bellville, Texas, outside Houston. His health problem wasn’t related to COVID-19, but Wilkinson needed advanced care, and with the coronavirus filling up intensive care beds, he couldn’t get it in time to save his life.

“He loved his country,” his mother, Michelle Puget, told “CBS This Morning” lead national correspondent David Begnaud. “He served two deployments in Afghanistan, came home with a Purple Heart, and it was a gallstone that took him out.”

Last Saturday, Wilkinson’s mother rushed him to Bellville Medical Center, just three doors down from their home.

But for Wilkinson, help was still too far away.

CBS News

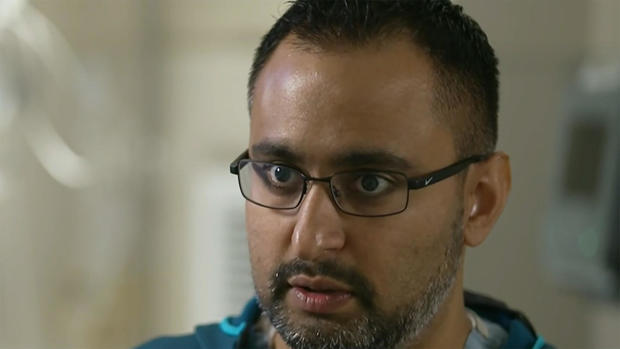

Belville emergency room physician Dr. Hasan Kakli treated Wilkinson, and discovered that he had gallstone pancreatitis, something the Belville hospital wasn’t equipped to treat.

“I do labs on him, I get labs, and the labs come back, and I’m at the computer, and I have one of those ‘Oh, crap’ moments. If that stone doesn’t spontaneously come out and doesn’t resolve itself, that fluid just builds up, backs up into the liver, backs up into the pancreas, and starts to shut down those organs. His bloodwork even showed that his kidneys were shutting down.”

Kakli told Begnaud that his patient was dying right in front of him. Wilkinson needed a higher level of care, but with hospitals across Texas and much of the South overwhelmed with COVID patients, there was no place for him.

Kakli recalled making multiple phone calls to other facilities, only to get a lot of, “sorry … sorry … sorry,” in reply. Places had the specialists to do the procedure, but because of how sick he was Wilkinson needed intensive care, and they didn’t have an ICU bed to put him in.

“Then I’m at my computer and, I’m just like, scratching my head, and I get this thought in my head: I’m like, ‘What if I put this on Facebook or something, maybe somebody can help out?’ One doctor messaged me: ‘Hey, I’m in Missouri. Last time I checked, we have ICU beds. We can do this, call this number.’ The next guy messages me, he’s a GI specialist, he goes, ‘I’m in Austin. I can do his procedure, get him over.’ I said, ‘Okay great, let’s go.’ He texts me back five minutes later: ‘I’m sorry. I can’t get administrative approval to accept him, we’re full.'”

CBS News

For nearly seven hours Wilkinson waited in an ER bed at Belville.

“I had that thought in my head: ‘I need to get his mother here right now,'” Kakli said. “I said, ‘If he doesn’t get this procedure done, he is going to die.’

“I also had to have the discussion with him. ”Dan,’ I said, ‘if your heart stops in front of me right here, what do you want me to do? Do you want me to do everything we can to resuscitate you and try and get your heart back? If that were to happen, Dan, if I were to get you back, we’re still in that position we’re in right now.'”

“He said, ‘I want to talk to my mom about that,'” Kakli told CBS News.

Finally, a bed opened up at the V.A. hospital in Houston. It was a helicopter ride away.

Kakli recalled Wilkinson saying, “Oh, man, I promised myself after Afghanistan I would never be in a helicopter again! … Oh, well, I guess.”

Wilkinson was airlifted to Houston, but it was too late.

“They weren’t able to do the procedure on him because it had been too long,” his mother told Begnaud. “They] told me that they had seen air pockets in his intestines, which means that they were already starting to die off. They told me that I had to make a decision, and I knew how Danny felt; he didn’t want to be that way. And, so, we were all in agreement that we had to let him go.”

Roughly 24 hours after he walked into the emergency room, Daniel Wilkinson died at the age of 46.

Kakli told Begnaud that if it weren’t for the COVID crisis, the procedure for Wilkinson would have taken 30 minutes, and he’d have been back out the door.

“I’ve never lost a patient from this diagnosis, ever,” Kakli said. “We know what needs to be done and we know how to treat it, and we get them to where they need to go. I’m scared that the next patient that I see is someone that I can’t get to where they need to get to go.

“We are playing musical chairs, with 100 people and 10 chairs,” he said. “When the music stops, what happens? People from all over the world come to Houston to get medical care and, right now, Houston can’t take care of patients from the next town over. That’s the reality.”

As of last night, there were 102 people waiting for an ICU bed in the greater Houston area.

Harris County Judge Lina Hidalgo told Begnaud that she was prepared to open a field hospital, but as of Friday morning, hospitals in the Houston area were telling her they had extra beds — but not enough nurses. Seven hundred nurses arrived last week, but it’s still not enough to meet the demand.

[ad_2]

Source link