Using psychedelics to treat veterans’ PTSD

[ad_1]

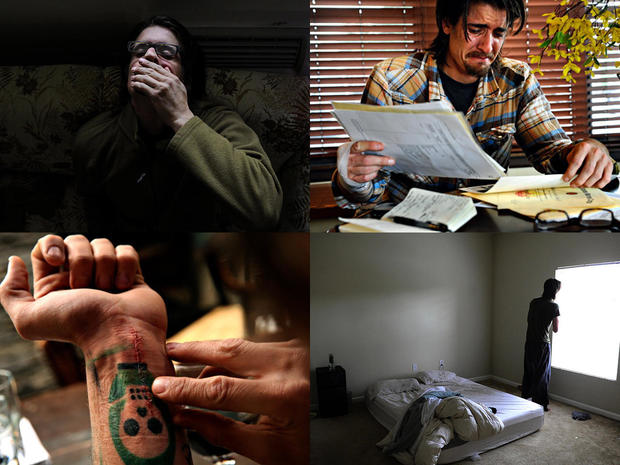

“I stabbed myself in the neck and the wrist with a knife,” said former Marine Scott Ostrom. “I just wanted the pain to stop.”

A series of Pulitzer Prize-winning photographs by Denver Post photographer Craig F. Walker captured the agony of Ostrom, his life overwhelmed by PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder) after two tours in Iraq … twelve years of nightmares, panic attacks and failed relationships … a danger not only to himself, but to others.

“Deep down I was angry, so really, I think, I was just looking for a fight,” Ostrom said.

Craig F. Walker

CBS News national security correspondent David Martin asked, “What were you angry about?”

“I was angry with myself. I felt guilty for some of the things that I failed to do when I was overseas.”

“Failed to do, how?”

“I watched my friend burn alive inside of a Humvee, and the fire was too hot and I couldn’t get to him, so I felt like I needed to be punished for that,” Ostrom said.

Rachel Yehuda, of Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, has spent 30 years working with veterans and other victims of PTSD. “You’re being haunted by a memory of something that happened to you,” she said. “The standard treatment for PTSD has been psychotherapy, and there are two medications that are FDA-approved for the treatment of PTSD, both of which are anti-depressants.”

“How effective is the treatment?” Martin asked.

“These treatments tend not to really solve the problem for most people, but they are better than nothing,” she replied.

Desperate for relief, Ostrom answered a Facebook ad seeking volunteers for an FDA-approved trial using a psychedelic drug called MDMA – better known by its street name, ecstasy.

“It really did change my life in a short period of time – six months,” he said.

CBS News

Yehuda said, “When I first heard about this, I thought to myself, ‘How could this possibly be a good idea?’ Psychedelics were illegal and designated by our government as being of potential harm and no medical benefit.”

Then, at the annual Burning Man Festival in Nevada, she met Rick Doblin, who heads a psychedelic research organization called the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), and for decades has been fighting laws which make psychedelics illegal.

“I knew that MDMA was great for PTSD in 1984,” Doblin told Martin. “When I think now about how many people over the last 50 years could have been saved from suicide or depression if the research hadn’t been shut down, it’s a tragedy.”

It was not until 2016 that the Food and Drug Administration authorized Phase 3 trials for MDMA – the same kind of Phase 3 trials COVID vaccines went through to prove they are safe and effective.

“The results from the latest Phase 3 trial of MDMA were just astounding,” said Yehuda. “Two-thirds of the people that were treated with a course of MDMA no longer have PTSD.”

“Would you call this a breakthrough?” asked Martin.

“I would absolutely call this a breakthrough,” she replied.

“What does the FDA think?”

“They’ve designated MDMA-assisted psychotherapy as a breakthrough approach. … It doesn’t mean you can start taking MDMA on your own; it means that the data are so good, ‘Let’s get this on a fast-track for approval.'”

But life on that fast-track costs money.

Doblin said, “The biggest obstacle really for us was raising the funds to do the research, because the pharmaceutical companies were not interested, the major foundations were not interested. It was all too controversial.”

Enter Bob Parsons, a maverick billionaire who first took psychedelics three years ago. When asked how much of a difference psychedelics made in his life, he replied, “The quality of my life has increased immeasurably.”

Never a good student, Parsons joined the Marines at 17 and was sent to Vietnam. A month later, he was wounded. It was the last he saw of combat, but the war continued to haunt him.

CBS News

“I was a completely different guy that came home than the guy that left,” he said. “The guy that came home, he had a short temper. Never felt like he belonged, no matter where he was or who he was with.”

Martin asked, “Was it getting better? Was it getting worse?”

“I believe it was getting worse. Somebody would ask me if I served in Vietnam, I’d start crying.”

Parsons made his fortune from an internet company called GoDaddy.com.

“So, now you’re a billionaire; what are you going to do with all that money?” asked Martin.

“I’m going to do what I can to get psychedelics approved for therapeutic use,” he replied.

Parsons has donated more than $7 million to psychedelic research.

Under the influence of MDMA, Scott Ostrom was able to actually visualize his inner demons: “This spinning black ball started to open itself up to me in different layers like an onion, and then each layer revealed, like, a new memory, and it was almost like the layers were just opening and opening and opening.”

Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies

At the center he found a part of him he calls “the bully.” It was, he said, “a terribly frightening creature.”

“So, the bully is basically the person you had to become in order to survive two tours in Iraq?” asked Martin.

“That’s right. That’s who the Marine Corps trains you to be – a fighter and a killer. And that’s who I had become to survive those deployments.”

With the aid of two psychotherapists, Ostrom was able to come to terms with it. “After those three MDMA sessions,” he said, “I haven’t had a nightmare about the war since.”

CBS News

“Do you suffer panic attacks anymore?”

“No.”

“Do you have any thoughts of suicide?”

“No.”

But like a drunk getting sober, he can’t undo all the damage done, all the years lost.

“You know, I spent over a decade pushing people away and making my life harder on myself and not loving myself,” he said, getting emotional. “So, as far as dealing with the combat part of my PTSD, we were successful in that, but I still think I can be a better person. I still think there’s room to grow.”

MDMA may be a breakthrough, but it’s a trial drug not likely to be available to the estimated one million veterans suffering from PTSD until 2024.

Yehuda said, “What the breakthrough means to me is that we have a meaningful way to spend our time now, so that we can bring a new paradigm of care to the people that need it most. It just means that there’s real hope out there. This may really end up being a game-changer for people that have suffered for way too long.”

For immediate help if you are in a crisis in the U.S., call the toll-free National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-TALK (8255), which is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. All calls are confidential.

Service members, veterans and their friends and family who need help can also call the Military Crisis Line at 800-273-8255 (press 1 for assistance), or text 838255. The Veterans Crisis Line is 800-273-8255.

For more info:

Story produced by Mary Walsh. Editor: Carol Ross.

Download our Free App

For Breaking News & Analysis Download the Free CBS News app

[ad_2]

Source link