The COVID frontlines: How NYC doctors faced the outbreak

[ad_1]

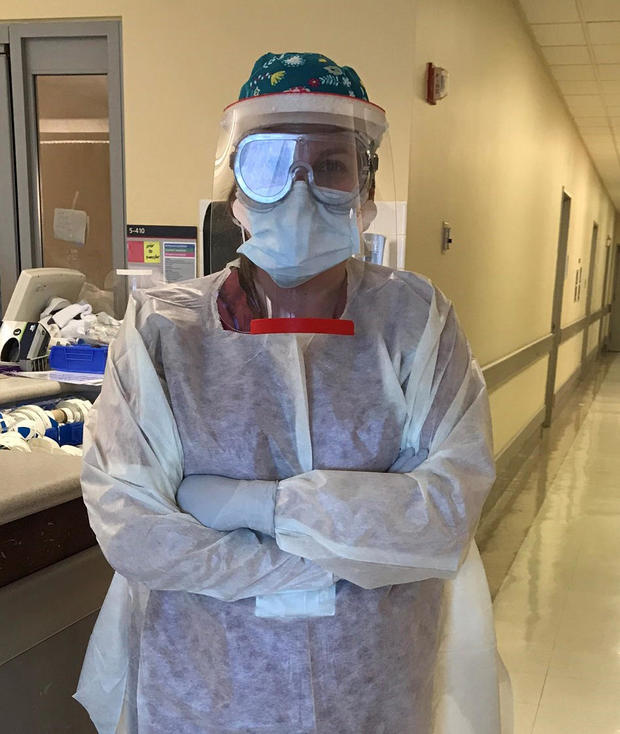

As head of a top intensive care unit in New York City, Dr. Lindsay Lief is no stranger to emergencies. “If the organs are failing, and you need to be placed on life support, you come to us,” she said.

When asked how much death she actually sees, Dr. Lief replied, “A lot. A lot.”

But in March of 2020, she saw more death than she ever thought possible, as COVID-19 stormed through New York-Presbyterian Weill Cornell’s 5 South unit.

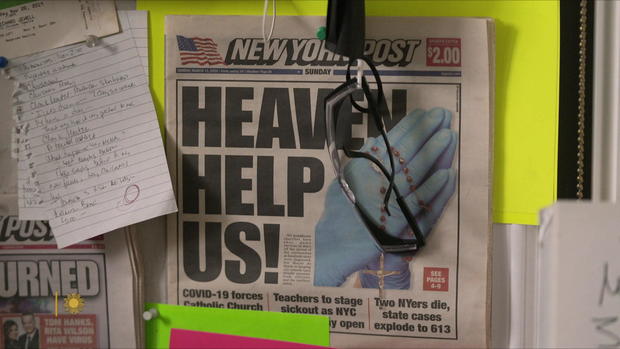

“We heard about hospitals sort of crumbling, like in Milan,” Lief told correspondent Lesley Stahl. “And we heard from colleagues there that there were patients literally dying on the floors of hallways with no oxygen. So, we had that sort of fire in our belly that that was not how it was gonna be here.”

But by April it was a war zone, with constant incoming. The number of COVID patients soared; ICU beds more than doubled.

New York-Presbyterian Hospital

“To have hundreds and hundreds of patients with the same disease on maximal life support, I mean, I remember walking floor to floor to floor,” she said. The whole hospital had essentially been turned into an ICU.

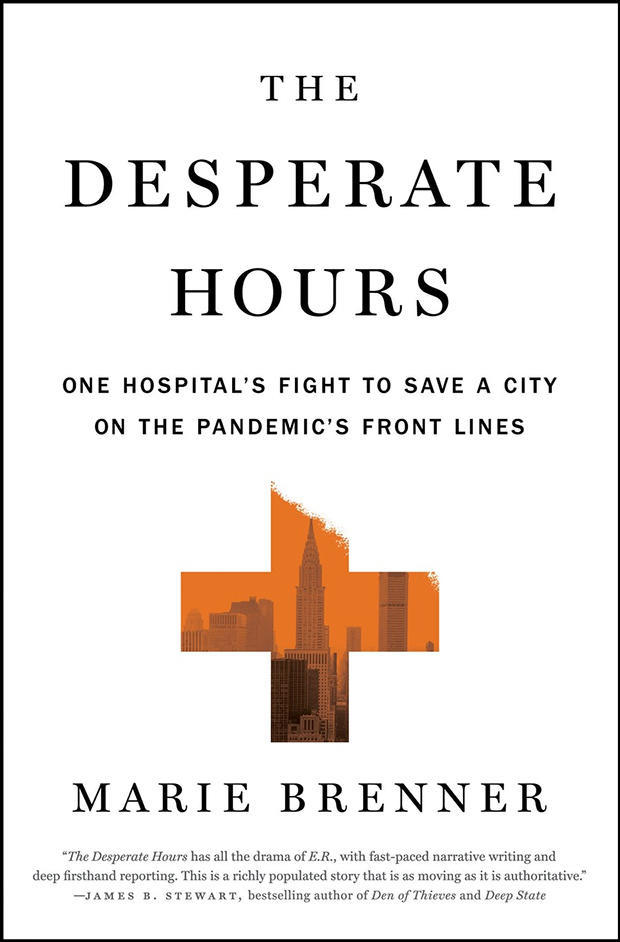

Journalist Marie Brenner’s new book, “The Desperate Hours: One Hospital’s Fight to Save a City on the Pandemic’s Front Lines” (published June 21 by Flatiron), describes New York-Presbyterian’s early heroic battle against the COVID pandemic.

There were no vaccines, no antivirals. Doctors were confronting the utterly unknown. “What they saw in that hospital was so disturbing to them, some of them still haven’t gotten over it two years later,” Brenner said. “When doctors of any caliber, but of this level of expertise, are confounded by a medical mystery, they are both enthralled, they are in full adrenaline, but on some level they’re also terrified.”

And overwhelmed. Lief said, “I worked probably two months without a day off.”

Stahl asked, “And then you go home at night. Do you actually sleep?”

“No,” she said. “Definitely not. When it’s quiet is when all those feelings and memories of the patients, or the colleague who was in tears, that’s when that all comes back. I barely slept.”

Yet, she still helped her two young boys with their homework over Facetime while struggling to run an ICU short on beds, masks, and everything else.

Flatiron

Brenner writes: “Had New York-Presbyterian crumbled, the damage to the nation and the world would have been many times worse than what we did experience.”

Karen Bacon knew she might die. She was not just another 5 South COVID patient; a Weill Cornell pediatric nurse, she was the first healthcare worker treated there for the virus.

Stahl asked her, “Right before you were intubated, what did you say to your husband?”

“‘I love you,'” Bacon replied. “I said, ‘You are now my proxy. So, you have to stand in for me and make the decisions, because I’m not gonna be able to make ’em for myself.'”

Dr. Lief said, “She was sick, and it was very upsetting, of course, for our staff to see one of our own in the bed.”

Just 30 years old and a newlywed, Bacon went from a cold in February to a ventilator in March: “I think the hard part was going to sleep and then finding out it’s two-and-a-half, three weeks later,” she said, having been in a medically-induced coma.

Like Bacon, every single Weill Cornell ICU patient at the height of April was intubated. All the while, there was a ventilator shortage.

“I have colleagues who to this day still I know talk about and think about decisions they made: who got the first ventilator? who got the first ICU bed?” said Lief.

Stahl asked, “Was there guidance from the leadership of the hospital?”

“We were told they were waiting from guidance from the governor,” she replied. “So meanwhile, my colleagues and I are, you know, making decisions with our best medical judgment in mind. However, you know, when someone with COVID died, which was every single day, of course, then you think, ‘What if they had gotten the third ICU bed and not the fifth ICU bed,’ right?”

CBS News

Dr. Ben-Gary Harvey, a 5 South pulmonary and critical care specialist, said, “In early 2020, I personally believed that we were all going to die.” And without the proper tools to confront this mystery illness, Harvey knew the only answer was innovation. He started with COVID patient Susie Bibi, who had been on a ventilator for four months. “She was at death’s door,” said Brenner. “She had huge holes in her lungs.”

Harvey had an unconventional idea: implanting a zephyr valve. Recently approved for emphysema, it works by stopping leaks in damaged lungs. But it had never been used at the hospital on a COVID patient – and many there rejected the undertaking as too risky. “I figured that if I found the leak in Susie, I can put some of those valves to prevent air from going into that part of the lung,” he said.

“But here’s the operative word there: If,” said Stahl.

“Well, what is the alternative?”

“She would not have survived?”

“I don’t think so.”

It worked. Said Harvey, “It just gives me the satisfaction that we can become creative, that we can continue moving forward, exploring new avenues.”

Brenner recalled Harvey saying, “If you stay in your lane when you are confronting this level of medical mystery, you’re not gonna solve it.”

When asked about Bibi’s status, Brenner replied, “She’s amazing. She was able, with help, weeks after she got out of the hospital, to be at her son’s wedding with her medical attendants, to walk down the aisle with people holding her.”

With so much death, victories were joyous celebrations.

Stahl asked Bacon, “What was it like the day you left the hospital?”

“They had everyone at the nurses’ station. They did the clap. They put a crown on my head. They just gave me the greatest sendoff.”

Stahl asked Brenner, “You know, we’re sitting here talking as if this thing is behind us. Is it?”

“Absolutely not,” Brenner replied. “But it’s enormously inspiring to know that, in the hospital systems, there are those who care so deeply, and who did save lives, at enormous cost to themselves.”

Noam Galai/Getty Images

For more info:

Story produced by Amiel Weisfogel. Editor: Carol Ross.

[ad_2]

Source link